Friends,

I hope that all is well with you and yours.

Things my end are better; although I am still in no shape to, say, run a marathon, at least I am at a point where I can think somewhat coherently. My days are thus once more filled with writing, be it the ABCDE framework book, the new whitepaper on eCommerce, or this newsletter. In fact, I have made it such a point of emphasis that I have left Stockholm for the next few weeks in favor of the inimitable tranquility of my house up north – and a rather improved “office” view:

More information about timetables and such will come as soon as I have them, though I can confirm that The Gravity of eCommerce will be released in September via WARC’s various outlets. I can also reveal that I will soon be making my return to MarketingWeek, providing the kind of market analysis and insight that, perhaps, is somewhat lacking in the present discourse.

But more on that later. Today, as promised, we are going to jump back into Cynefin.

So, with no further fuss or muss, here we go.

Previously on Strategy in Praxis

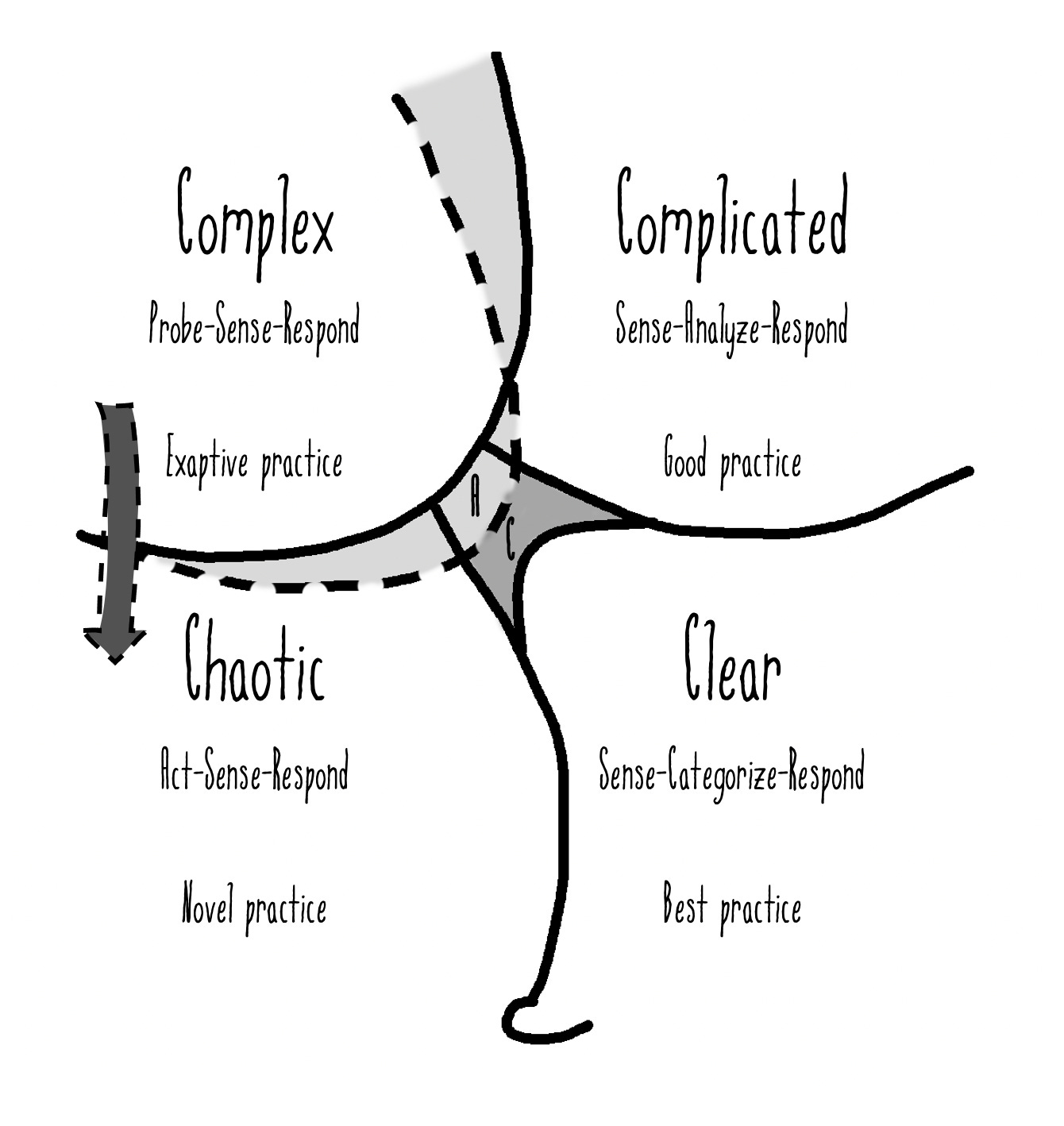

We introduced Cynefin, a sense-making framework created by Dave Snowden, two weeks ago. It is centered around the three kinds of systems that exist in nature (and, obviously, organizations): ordered, complex and chaotic.

Ordered systems, which are highly constrained, can be broken down into the Clear and the Complicated domains. In the former, causal relationships are obvious, solutions to problems are self-evident, and there is a definable best (better than all the rest) practice as a result. In the latter, causal relationships exist but are more difficult to spot – expertise is usually required. A number of approaches can solve any problem at hand; hence no single best practice exists, but good practice does.

The Complex domain, meanwhile, is demarcated not by linear causality but by disposition. That is to say, it is dispositioned to exhibit a certain pattern although there is a high degree of uncertainty. The lack of causality (and thereby predictability) means that we have to test things out – probe the system – and practice is consequently emergent or exaptive. To steal an example from Snowden, consider the difference between a Ferrari (complicated) and a Brazilian rainforest (complex).

In the Chaotic domain, lastly, cause and effect are entirely unclear. There are no patterns, no constraints, and any practice will therefore per definition be novel.

Implications for Strategy

Each of the domains, as should by now be obvious, demands its own particular strategic approach. To illustrate, if one is dealing with nonlinear complexity, hindsight will not lead to foresight as the context keeps changing. This means that, contrary to common consultancy claim, one cannot establish how X led to Y for company Z (and how any company that does the same will achieve the same results, conveniently with the aid of said consultants). It might be true for a Clear domain problem, but not a Complex domain one. In reality, the same company trying the same strategy at another point in time would not achieve the same result.

As we have discussed previously, the complexity-fundamental principle of the adjacent possible ensures that we not only do not know what is to come, but we cannot know. Consequently, attempts to meticulously plan ahead are, as Russell Ackoff once put it, no more than a ritual rain dance; it has no effect on the weather that follows, but it makes those who engage in it feel like they are in control.

But, at the same time, we still need constraints, lest we end up with incoherent movement, constant pivots and chaos:

So, it is clear that we do need strategy, and we do need boundaries that define the outer limits of strategic behavior, just not a plan consisting of little else than a straight line between the now and then – the messy present and the idealized future state – supported by incessant calls for alignment.

Planning is much better suited for ordered domains in which we know what works and what does not, where we can exploit existing knowledge, and where creative experimentation is not needed in the everyday. To borrow an example from Steve, none of us wants whoever is preparing our slightly more expensive cheeseburger at McDonald’s to start trying things out for the lols. But be careful not to over-constrain the system or you will risk falling into chaos:

It is for these reasons that, as we as we touched upon a fortnight ago, the Confused domain in the middle is so dangerous. If we erroneously believe we are in one domain when, in fact, we are in another, our strategic choices may easily end up hurting the business both short-term and long. Unfortunately, this is often what happens. Time after another, strategists, akin to the consultants in the example above, assume order, attempt to model the non-modellable, predict the unpredictable and plan for a future that only has, and only ever will, come to exist in their heads. Inevitably, something then happens that forces them to redo their plans and the cycle begins anew.

To reiterate, my point is not that nothing can be planned for; my point is that not everything can be. The Cynefin framework explains why. In reality, nothing is context free. Everything is context specific. There is as little value in going all-in on agile experimentation across every aspect of a business as there is in sticking to a plan regardless of what happens.

The potentially billion dollar question therefore becomes how one can know which aspects of one’s strategic challenge lies in which domains. Well, that is what we are going to be discussing next week – including one simple-to-use method that anyone and everyone can start doing immediately.

Until then, have the loveliest of weekends.

Onwards and upwards,

JP

This newsletter continues below with a market analysis exclusive to paying subscribers. To unlock it, merely click the button below.