Friends,

I hope that all is well with you and yours, and that this e-mail finds you on a boat with shoddy connection, in the tropics, three months after I sent it.

NEW PRESENTATION KLAXON

I have recently added a new talk to my repertoire (see further details below): what complexity science tells us about marketing. The presentation sets the theoretical foundation in easy-to-understand terms, then explains in simple-to-follow instruction what to do as a result. A keynote by design, it should open the audience’s minds to a whole new way of thinking - enabling them to take smarter (and more valuable) action.

Its title?

The next paradigm.

How to level up your marketing with Nobel Prize winning science.

Still on the menu:

What to do when you don’t know what to do.

How to create a sustainable competitive advantage through superior adaptability. (Based on the new book by the same name.)

Succeed big, fail small.

How to use experimentation to drive efficiency and effectiveness of innovation at scale.

Toward a fourth kind of uncertainty.

What new science reveals about old ideas.

If you want to book me for your event, corporate speaking slot, or workshop, merely send me an email. To make sure I am available, please do so at your earliest convenience; my availability is limited and the schedule tends to fill up fast. More information may be found here.

The TL;DR

Today, James Hankins provides a practitioner’s insight newsletter to conclude the theme of planning. He argues that:

There are many forms of planning, and understanding the how they all fit together is instrumental for most strategists in practice.

The three most important variants are strategic planing, operational planing, and executional planning.

Sorting action on RGU and strategic priority will help planners to make sense of what they need to do in the short-, medium- and long-term, respectively.

The corporate reality is generally more about small increments than wholesale shifts.

Ultimately, whether they work or not, plans are required in the modern corporate setting.

Personal updates before we go-go

Just throwing this out there.

I am going to build a framework, complete with a step-by-step practical guide, for how to manage uncertainty. The more I continue to work in the field, the more I become convinced that:

a) It appears to be what one might somewhat self-aggrandizingly call “cutting edge”; as far as I can tell, there is precious little out there like it. That may, of course, mean that I am getting everything wrong, but so far, the theories have matched reality with very impressive accuracy.

b) The work will have crucial implications for businesses in general - it has immediate consequences for strategy, innovation, risk management, resilience engineering, and more - and financial firms in particular.

However, I cannot afford (in literal terms) to set aside time to finish the work if it is to be finished before Christmas. Thus, if there is a company out there that wants to get ahead of the pack by becoming a corporate sponsor (with all the benefits that one would expect to follow), do let me know.

On the topic of my work, the new keynote is a result of many long conversations with Doug Garnett. This week, we began to dig deep into marketing from a complexity scientific angle and, well, l felt I had no choice but to make a talk about it. It holds such immense explanatory power.

The topic is obviously one that I have worked with for quite some time; I have also written extensively on it. But recent insights have taken it to a whole new level. In fact, there are so many potential penny drops in the keynote that, if I do it justice, it should make the audience gasp.

For instance, the presentation explains why there is a gap between the EBI and the more traditional marketing schools, where the gap actually comes from, why the current discourse will never bridge it, but how new scientific discoveries can.

As an increasing number of people attempt to take advantage of AI solutions, it becomes painfully obvious how few actually know how to use them properly. If I have to see another strategy deck clearly made with ChatGPT, I am going to scream.

Do not get me wrong, AI can be very helpful if utilized correctly; I use it to criticize my own work, for example. But it should never be fully trusted. Always confirm its claims; always do your own homework; always keep in mind how often it hallucinates. Because if you do not, someone like I will, and the consequences will most likely be dire.

Moving on.

The market vitals

Tesla is becoming a rather, shall we say, interesting case study of what moves (and does not move) stock prices, and the broader public’s response.

On June 30, shares dropped as Musk attacked Trump’s tax bill, calling it “utterly insane and destructive”. The long and the short of it is that the bill would end tax credits for EV purchases after September, which is quicker than the House original proposal’s of the end of the year.

On July 2, Tesla revealed that it had suffered a 13.5% YoY drop in quarterly vehicle deliveries - the worst decline in the company’s history. The stock rose.

Clearly, the forces at play here are, as ever, expectations. The tax bill is looking to have an impact on future sales. The sales that have been have already, well, been, which is why the stock went up when the drop was awful but not as awful as forecast.

Obviously, a stock's price represents its present value, reflecting what buyers are currently willing to pay for it. But equally obviously, this price is influenced by expectations of future returns. This is basic, but always worth remembering when people without any kind of baseline understanding make grand and often hyperbolic claims about how a company most certainly does or does not deserve its present valuation.

There is an interesting juxtaposition in the US economy at the moment.

On one hand, it is showing signs of “landing softly”. The tariffs have not yet had much of an impact on inflation, and the stock market is doing reasonably well (if nothing else, it appears to be more balanced). The recent nonfarm payrolls report was also solid: according to the Labor Department, 147,000 jobs were added in June, well above the expectations of 117,500. Although overall growth is decelerating, the case for immediate rate cuts is pretty much null and void for the time being.

On the other, the Fed lacking a reason to cut rates also means that Trump will continue to berate Powell for not taking action (even though his wait-and-see approach clearly is entirely justified).

On his own part, the Orange One seems hellbent on making the economy worse. From continued tariff volatility to tax bills that increase the federal budget deficit significantly, it is clear that financial resilience should remain a strategic imperative for US firms for the foreseeable future.

The Senate this week rejected a provision in the megabill that would have limited states’ ability to regulate AI, which Barron’s took to constitute a “crushing blow to tech giants like Meta and Microsoft”. I am not so sure.

Although a block on state limitations in AI technology would have meant a proverbial free-for-all, allowing states to “oversee AI as they see fit” will merely mean that companies will shift to whichever state is the most lenient. Texas, for example, is already doing its best to embrace big tech. What is to say that they will not therefore ensure that they are the most AI friendly state?

Moving on.

All parts of the plan

Part IV

As we conclude the first part of the Strategy Omnibus, we do so with another practitioner’s insight. This week, it comes from James Hankins - a man who, at this point, needs no introduction.

When JP and I had a conversation about this week’s newsletter, my initial thought was “should I use AI to help me write?”. I must admit that whilst I’ve used the various different LLMs over the last couple of years I still hesitate towards putting my writing/IP into the training data. Ignoring the company use of Microsoft (co-pilot never works anyway), this conscious course of action (or a “plan”) is arguably pointless up to and including the moment when the various LLMs have to explicitly request permission. In a vain hope and attempt, I tend to therefore drop certain paragraphs in and remove identifiable data - and that’s what I plan to do here.

The plans and the parts

So why am I writing this, and what is “planning”? Well, the brief was “a practitioner’s view of planning”, and a quick look at my CV says I should understand it (planning) intrinsically. I started my career as a media planner/buyer; a mystical creature in the modern day, a media practitioner was someone who decided which media was most appropriate (using primarily performance analysis, because I was a direct response planner/buyer) before negotiating the cost of the space and ultimately faxing through the confirmation. Then, there were 14 years as a comms planner/comms strategist before, most recently, a role as the Global Vice President of Marketing Strategy and Planning at a big B2B SaaS corporate. This included leading the corporate strategic planning process and contributing to the most recent corporate strategy review.

Hopefully, then, I understand “planning”. But I also understand strategy, meaning that I know the difference, what often happens from a practitioner’s POV, and how that has evolved my behavior and understanding.

JP has, of course, written about planning over the last three weeks (and referenced it ad infinitum in six years or so that I have known him). The difference between planning and strategy is also well documented, although having read company reports for a number of years, it’s clear that there is often a blurring of the lines between the two in practice.

In my experience, strategy can become something that merely occupies the written word whilst planning supersedes any strategic restrictions; it therefore becomes the de facto decision-making tool that relates to “things people do”, especially in the short term. Part of this can be explained by the fact that planning is able to contain multitudes whilst strategy is, by definition, constrained. This, I think, is what causes the problems; there is much that happens in business which is not strategic but nonetheless must occur. And this is fine, to a point.

A simple illustration would be the presence of an old product that still delivers revenue. On the face of it, and with certain business models, this shouldn’t be a problem. However, in my most recent role, repeatable revenue was incredibly important. As a subscription business it (repeatable revenue) provides the lion’s share of the total revenue.

Customers may be on an old product, paying subscription fees (probably higher than newer iterations too) and having built people and processes around software. This makes the product incredibly sticky (please don’t get me started on how every corporate ever is going to drop its current software systems immediately due to genAI; a laughable proposition that demonstrates a clear lack of business understanding). No matter how this product-and-revenue combination is mitigated, a plan will be required even if it’s not strategic. End-of-life-ing is unlikely to be an option within a twelve-month horizon, and a migration pathway is undesired because the risk in losing that revenue creates a hole that needs to be filled by new customers and/or increased revenue from other existing customers. See my previous point: “plans contain multitudes”.

Various kinds of planning

One of the key aspects I noted as a practitioner was the potential confusion the word plan/planning can create. What is the purpose of the plan and to what end are we planning? In the end I had to mentally categorize the type of planning or plan that I was being asked to develop so that I could better execute to the brief. Although this may sound simple, it took me a while to work out, and included pulling a number of colleagues quietly to the side to ask “what sort of plan?”.

Ultimately, the issue resolved itself in my head as three types of plan/planning that occupy business life:

Strategic Planning

Operational Planning

Executional Planning

(I’ve consciously not numbered these as they are conceptual, NOT sequential.)

First things first, what is strategic planning?

Strategic planning is kind of an industry in and of itself, but conceptually and in practice, it really should only refer to a) the market scan (analysis), and b) an understanding of ambition (to support strategic goals) including the key initiatives that should propel the business towards its current strategic horizon. The issue with strategic planning is that it’s often solely focused on delivering a number (even in functions where accountability is not a number) - a fact which can be particularly impactful in non-market orientated organizations, because quite often (i.e., always), the market determines performance. The internal estimates of performance do not.

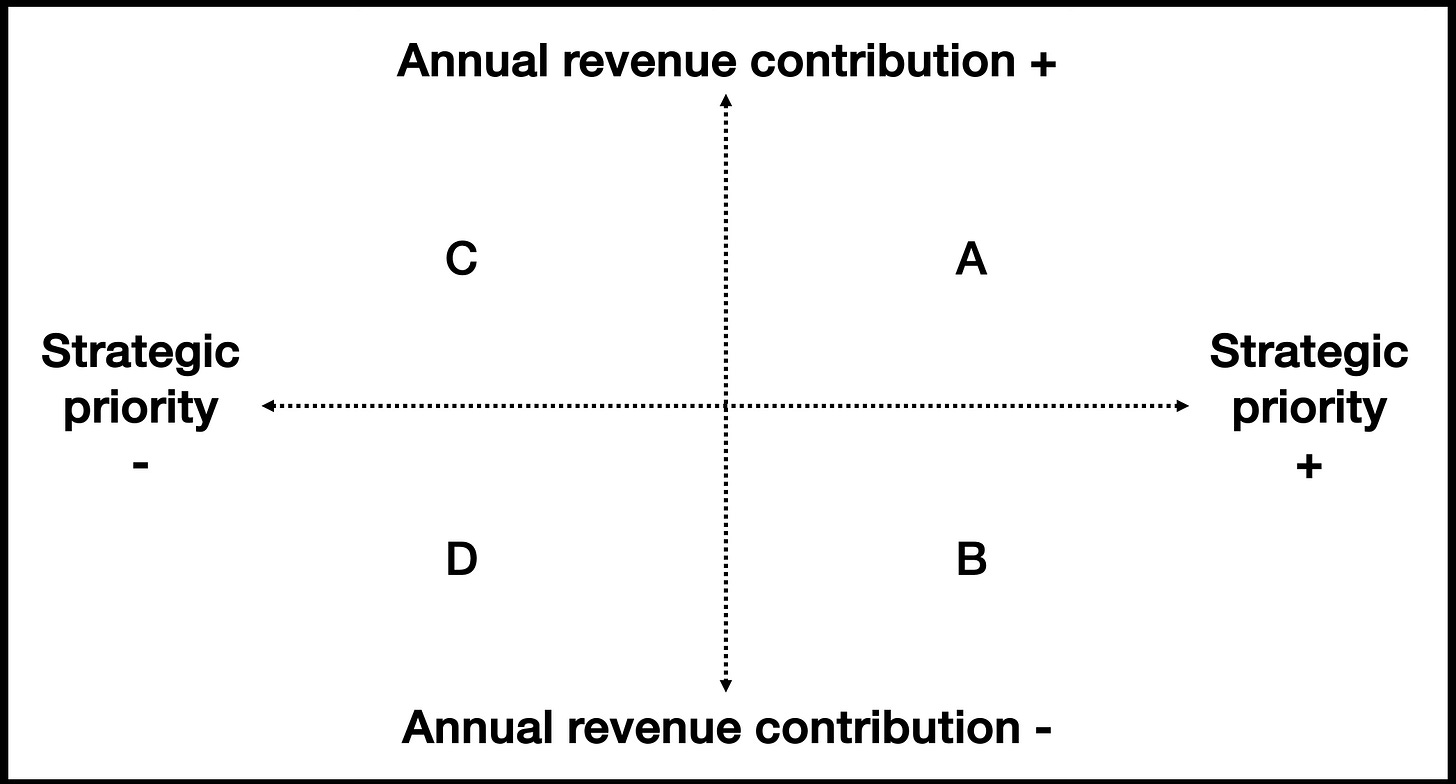

Strategists are fond of their tools and to help them prioritize I developed a simple two-by-two (not dissimilar from the Boston matrix) that articulates initiative/RGU (revenue generating unit) strategic importance vs size of business unit including growth rate. Its purpose is to help drive alignment:

The grid contains four areas of focus.

A – Large RGUs with high strategic importance (usually in a market with reasonable growth).

B – Small RGUs with high strategic importance: the future of the business (which requires investment).

C – High RGU with low strategic importance. Lower levels of effort, but maintenance required.

D – Low RGU with low strategic importance. Low levels of effort.

I know there are strategists out there who say that models and frameworks are of no use. I imagine they have never worked corporate side. Models are useful to frame conversations, and strategy (in its modern guise) is about stakeholder engagement rather than ivory tower pontificating.

The quick amongst you will realize that the real debate comes between B and C. A is a fait accompli - just do it - and D is also a fairly straightforward. When working out whether the ambition is realistic, it should be validated against the contribution provided within these tradeoffs, forcing strategy and strategic planning to work effectively.

Naturally, the B and C tradeoffs are centered around the truism that some RGUs are strategic and the fact that not all strategic “initiatives” are revenue generating in the short term. The balancing act that follows should enable resources to be apportioned strategically to areas with little immediate revenue pay back BEFORE budgets are subsequently focused on delivering the ambitious strategic plan; it forces stakeholders to engage in strategic planning for the benefit of the short and long term.

A top down “validated” ambition should then be based on the tradeoffs above with a number of key principles applied:

Market growth rates. Ideally the floor, but if a company is below average it may merely be improvement on YoY numbers.

Market share. The most recent year’s performance is likely to be the best representation of the near future performance (all things being equal).

A performance dividend based on “over-performance” against market share, i.e., penetration gains (hopefully).

Industry and internal comparison ratios are useful. Do you really think that you can outperform every benchmark in the competitor set? What makes you believe that could be true?

Remember, strategic planning is really an AMBITION, which is different from what investors are going to be told, as it should create a stretch which is attainable but probably out of reach. By contrast, profit or growth warnings are NOT good for the business, so attainment is always tempered externally. Ultimately, this is what underpins the OKR (Objectives and Key Results) methodology, i.e., 70% achievement is good.

Executional planning is different

The next concept is where there arguably is the largest potential for misalignment. It is also where I struggled as I got confused when asked about “the marketing plan”. Is this the set of things that marketing is going to put into market? Is it the things that will enable the aforementioned? Is it both? Is it neither?

A “marketing plan” to me was/is a set of executional decisions. It’s the aforementioned executional plan (or plans) that details WHAT is going to be done in order to help deliver the ambition; the classic “bottom-up” assumptions and detailed courses of action. While it remains true that context defines the performance of these plans, in a great many cases the plans are extensions of what recently already has happened - performance is largely looked at within a twelve-month period. Most meaningful things in business don’t change too much or that quickly, and the best way to create problems is to try to change too many things. The corporate reality is generally more about small increments than wholesale shifts.

Ultimately, the executional marketing plan concerns itself with the strategist’s thoughts as they hit the customer and the enablement of that thinking. One may, obviously, replace the marketing department with any other. Either way, executional planning is “the things we will deliver”; the output, not the outcomes.

The other one – what is the operational plan/planning?

Finally, we have the operational plan/planning and I’d like to think I have breadcrumbed it. It is probably the most undervalued form of planning, not least because of how rarely it is discussed. Neither its existence nor what was required was immediately obvious to me.

If the strategic plan is the ambition setting, a quantified set of figures/expectations, and the executional plans provide the details that delivers upon that, what is the operational plan?

From my experience, the operational plan is the one which knits it all together. It’s the realm of project and change management, of Gannt charts and stakeholder mapping, of processes and workflows. It’s the step-by-step guide that sets the operational process under which the strategic process moves to the executional planning stage, the multiple feedback loops, and stakeholder engagement. It’s the part that requires human understanding and influence management, the realm of the nemawashi (pre-plan buy-in) and the side conversations. The outcomes are captured as other plans, but ultimately the metric through which operational planning is measured is linked to the efficiency of its process.

Operational plans ultimately allow management to orientate the output planning process to the executive and be clear to all stakeholders which decision stages are left to get through. They also allow for constant optimization and feedback loops; plans should evolve naturally as new restraints emerge.

Put differently, then, operational plans are the “water carriers” of the organization; the documented workflow from strategy to execution. They are the reason why there are such qualifications as a Project Management Professional certification and PRINCE2 (PRojects IN Controlled Environments), and the key to effective delivery of planned projects - while distinct from the overall ambition and detailed executional “outputs”, both of which resolve themselves as “plans” but in a very different way.

So, is planning important?

Roger Martin, JP, and others, like to tell us that “a strategy is not a plan”, and it has subsequently become a truism that, in business, these two concepts often get confused. Complexity theory tells us that planning is arguably less important than understanding that plans fail all the time, to work with that knowledge, and manage the potential for change (a plan in and of itself) because life doesn’t work to pre-conceived ideals. To me, this is probably the crux of the matter. Planning is not just fundamental to business operation, its arguably core to the human condition: humans, above all, plan. They naturally look to the future and create fixed settings based on the destination. Thus, as far as I see it, it is not about planning being a problem as such. After all:

Try getting investment without a business plan.

Try telling your boss what you’re doing next year to deliver revenue without one.

Try engaging multiple stakeholders without a roadmap.

Plans ultimately form the core of business organizations; they corral and structure, channel thought and action into a controllable field. But it's important to understand that plans do and will fail. The future is unknown and things change; it is imperative to understand and plan for it.

And with that, we thank James for his contribution. Next week, we will start to look into Porter’s positioning school of strategic thought.

Until then, have the loveliest of weekends.

Onwards and ever upwards,

JP