Friends,

I hope that all is well with you and yours.

Not a quick update as much as a story before we go-go

As you are reading this, I am driving down to the southern-most parts of Sweden on a short Easter holiday of sorts; my sister-in-law has turned 30, so we will be spending the weekend with her and her family. Normally, being an independent consultant and therefore getting nothing, so to speak, for free, I would have brought my laptop and spent any spare time working. This time, I have not.

The reason is the much, much overdue (and painfully obvious) realization I shared on LinkedIn this past Saturday. When we spend our lives running at full speed – which so many of us do, either because we are forced to or because we feel that we are – we stand a real risk of not merely missing sights along the way, but also leaving what matters most behind.

I still work a lot, and the evidence suggests that I am pretty good at what I do. But no strategy I ever create, no book I ever write or any presentation I ever make will be as memorable as a single morning, playing with my laughing daughter in the sun and snow.

And that insight makes me rather happy, to be honest.

In the news

Hermès is now worth more than Nike, with the former coming in at a $218B market cap and the latter at $188B. There are reasons why, of course, such as ease of access to increased free cash flow, but more than that, the figures once again demonstrate the pointlessness of so-called brand valuations.

Walmart is looking to robots to help the company grow by more than $130B over the next five years, primarily by having the robots unload pallets and fulfill orders. While a smoother, more efficient supply chain theoretically could enable the company to increase high-margin revenue streams (e.g., advertising), provided that it also ensures a larger e-com customer base, it seems a lot more likely to “merely” save costs.

Alibaba is splitting into six companies and explore IPOs, thereby officially moving on from the Jack Ma era. On a surface reading, the move makes sense for almost all parties, well, perhaps save one.

Item of the week

Wiemer Snijders, a friend of Strategy in Praxis, recently shared an excellent critique of Jonathan Haidt’s research on teenage depression called The Statistically Flawed Evidence That Social Media Is Causing the Teen Mental Health Crisis by Aaron Brown. Beyond the topic itself, it is a masterclass in how to assess the quality of research. I highly recommend the read, as well as the key paper that it references (Why Most Published Research Findings Are False, found here).

The statistical fallacy that drives this paper is sometimes called "assuming a normal distribution," but it's more general than that. If you assume you know the shape of some distribution—normal or anything else—then studying one part can give you information about other parts. For example, if you assume adult human male height has some specific distribution, then measuring NBA players can help you estimate how many adult men are under 5 feet. But in the absence of a strong theoretical model, you're better off studying short men instead.

This is sometimes illustrated by the raven paradox. Say you want to test whether all ravens are black, so you stay indoors and look at all the nonblack things you can see and confirm that they aren't ravens. This is obviously foolish, but it's exactly what the paper did: It looked at non–social media users and found they reported never feeling signs of depression more often than expected by random chance.

Moving on.

McKinsey’s 7S model

The map is not the territory

As we know from previous newsletters, the late 1970s and early 1980s can be said to be the golden years of strategic management frameworks. Bruce Henderson and Alan Zakon were busy flogging the BCG matrix, Michael Porter had just released Competitive Strategy, Peter Drucker still had another twenty odd books in him, and McKinsey would be damned to be left behind. Although they had developed a 3x3 matrix for General Electric (more on that in a future newsletter), clearly, there was a need to strike again while the iron was hot.

Consultants Tom Peters and Robert Waterman (alongside a few colleagues) provided the proverbial blow. Instead of looking at parts of the organization in isolation or, conversely, discussing the firm as if it were one whole, they sought to define how various parts of a company were connected to one another.

It was, one must admit, a stroke of genius. The 7S model that came out of their work, first presented in In Search of Excellence (1982), not only solved the problem with Porter’s five forces (which, some may remember, exclusively featured the external; Porter corrected the issue with his generic strategies three years later), but its success also guaranteed more work. After all, if parts of a company are connected, it stands to reason that changing one means changing all, and more consultant hours will inevitably be required.

Anyway.

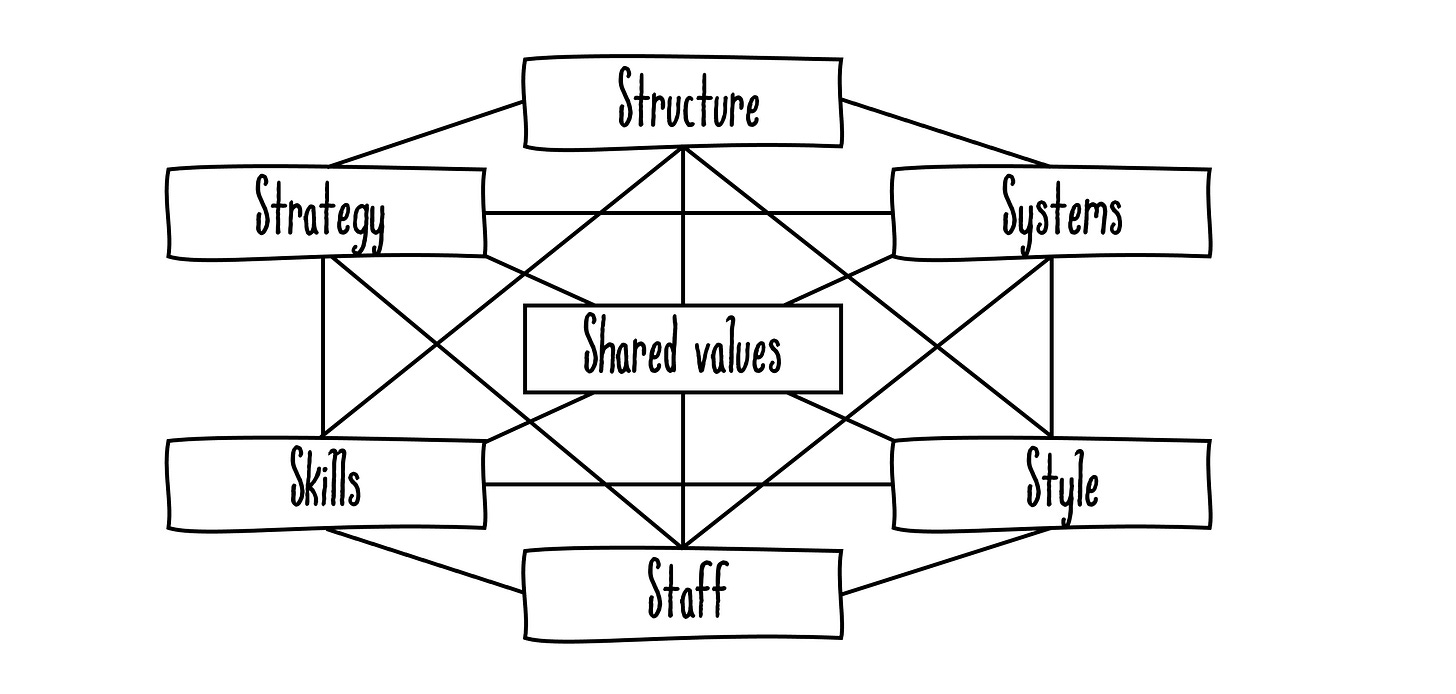

At its core, the 7S model consists of six dimensions connected by shared values.

Strategy is best understood as a plan; the alignment of resources and capabilities to gain competitive advantage.

Systems are infrastructures used, be it technical or otherwise, by employees on daily basis. They can be formal or informal.

Structure is how the company is set up, including roles, responsibilities, integration, and division of activities.

Shared values are what the organization, and by at least theoretic extension its employees, believe in; missions, visions, culture statements, and so forth.

Skills can be defined as core competencies and capabilities.

Style is how leaders and managers behave; the “culture of interaction”.

Staff, lastly, is human capital.

Should you ever need to use the 7S model in practice – which, contrary to popular belief, may actually happen – there is, as so often is the case when something has been around for a long time indeed, plenty of how-to pieces easily available online.

However, for the purposes of this newsletter, I will not go into detail here and now. Then what, you may ask, is the purpose for your discussing the model at all, if that is all that we will cover?

I bring up the 7S model because it perfectly encapsulates a problem with models and frameworks that many fail to see until it is too late.

On a surface reading, the model appears innocuous enough; it provides a landscape format snapshot of the organization. Although it fails to cover everything that is, or provide insight into what can or will be, most with practical strategic experience know that there is a difference between the static and the dynamic. The primary use of the model, therefore, is to serve as a rudimentary reminder of sorts.

But actually filling in the blanks – the 7S – can be immensely difficult. Any strategic planning school of thought may go into “Strategy”, and with each will come all kinds of challenges. The same is true for “Skills” and core competencies; “Systems”, “Structure”, “Staff”, and the resource-based view; “Shared Values” and, well, your guess is as good as mine. The list goes on. The only viable conclusion is thus that it is a model designed not to help the company, but to help a consultancy (McKinsey) sell services.

In a way, this also means that the 7S are the opposite of what a framework should be. I sometimes receive critique for my theoretical work being hard to comprehend (a very famous professor recently quipped “it is all lovely, but fucking complicated”), but the point of it all is to provide a rock-solid foundation for subsequent practical implementation that is extremely easy. It is not necessary to know said theory in order to implement ABCDE in practice; I am merely playing with my cards open.

By comparison, models like that of Peters and Waterman rely on their initial simplicity, but are quickly discovered to be anything but simple to put to use. Not only does one have to move from practice to theory (as per above), but there is also no guidance on, for example, how the seven elements are aligned, prioritized, or might change over time. You need a consultant to tell you that.

The dean at my law school once joked that lawyers are like a virus; the more lawyers there are, the more problems there will be, the more lawyers will be needed. On and on it goes until the profession becomes self-sufficient. The same could be said for management consultants. Oh, the irony that I have moved from one profession to the other.

Next week, we will take a look at PEST and see whether it fares better. Until then, have the loveliest of weekends.

Onwards and upwards,

JP

This newsletter continues below with additional market analyses exclusive to premium subscribers. To unlock them, an e-book, and a number of lovely perks, merely click the button. If you would rather try the free version first, click here instead.